Blog Feed

Why Did "The Ocean is Broken" Go Viral?

In late October, we saw a big, sustained spike in online attention to an article that came out in the Newcastle Herald, entitled “The Ocean is Broken.” The story chronicles ocean yachtsman Ivan Macfadyen’s experience retracing a trans-ocean journey he had sailed 10 years ago, and his shock at the profound decline he saw in sea life and ocean health. According to the Herald, the article “smashed Fairfax Regional Media records.” The article, definitively lacking hard science, clearly struck a chord with readers worldwide, and Macfadyen is now fielding requests for interviews, letters from concerned citizens, and offers from documentary filmmakers to help tell his story.

Our community of ocean lovers and ocean communicators was intrigued, so we decided to don our Upwell analysis hats and put our Big Listening tools to the test, to answer a couple key questions. First: Why did this story, above all the others that talk about ocean health, go so big? And second: What can Team Ocean learn and apply to our work?

The Numbers

"The Ocean is Broken" has been shared over 115,000 times on Facebook and Twitter, and is still being shared now, a month after it was originally published. In fact, in just the last week, the story has been shared between 40-80 times per day.

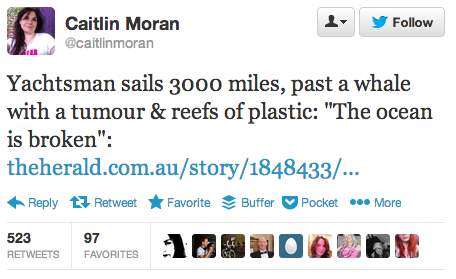

The story was first shared midday in the UK on October 18 (early am in the US), but didn’t achieve real momentum until it was shared by Caitlin Moran on Twitter on October 20. The British media personality and author has 470,000 followers on Twitter, and is known for her humorous (and often NSFW) tweets and her high level of engagement with her followers.

Several other Twitter "celebrities," including Twitter founder Jack Dorsey, shared the story but it seems this tweet was what tipped the initial scales.

The story did exceptionally well on Facebook, with over 100,000 shares, nearly 100,000 comments, and over 85,000 likes, heavily overshadowing numbers on Twitter. (Source: SharedCount)

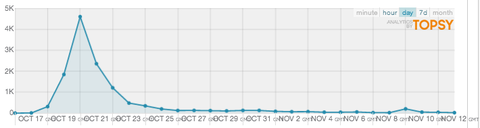

The shape of the “spike” is much wider than similar stories would be. This means there was sustained volume over several days, and the story had legs for much longer than 24 hours. Indeed, Twitter conversation levels in the past week have remained in the 40-80 mentions per day level. (Source: Topsy Pro)

A story with real legs: Twitter mentions of “The Ocean is Broken” Oct 17-Nov 13.

It's a human interest story.

The data above tell only part of the story. The heart of the story lies in understanding why the initial people who read "The Ocean is Broken" decided to proactively share it with their friends, followers, readers and fans. With articles coming out every week that tell us oceans are hurting, why did this one go viral?

One thing that's important to distinguish is that this is not a science story, or an environmental story. It is a human interest story. The author, Greg Ray, was not writing an article about ocean health. He was recounting and sharing the powerful personal anecdotes of Ian Macfadyen.

When we, as conservationists and scientists, want to connect people to an issue we find important, such storytelling is a powerful tool. A story can bring a wonky issue to life. Take, for instance, the health care reform law (Obamacare). Journalists, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies are relying on storytelling to connect with people. A story about how someone who had been previously denied health coverage due to a pre-existing condition is much more interesting than an article detailing all the changes in the new law.

Scientists are often trained out of including narrative or anecdotes in their writing, but this is a reminder that that reluctance to get personal can come with a cost.

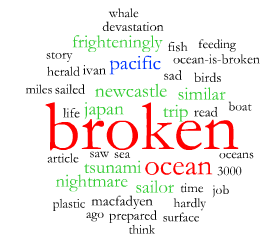

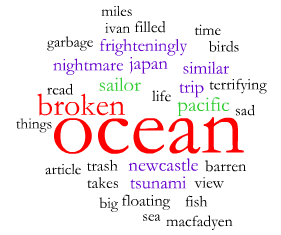

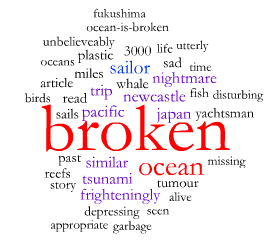

Not only did "The Ocean is Broken" tell a story, it was able to incite emotion. With Radian6, we were able to get a better understanding of people's reactions to the article, en masse. The below three word clouds represent the three days that saw the highest volume of sharing.

Note that the emotive words are closely related: nightmare, frighteningly, terrifying, disturbing. With lower frequency we see words like sad and depressing. While positive emotions tend to spur social sharing at a higher rate than negative emotions overall, it is also the higher energy emotions that spur sharing. Fear is a higher energy emotion than sadness. The language used in the article, from the very beginning paragraphs, is clearly meant to evoke these nightmarish fears:

The wind still whipped the sails and whistled in the rigging. The waves still sloshed against the fibreglass hull.And there were plenty of other noises: muffled thuds and bumps and scrapes as the boat knocked against pieces of debris.

The article is also written for the web: short paragraphs that make scanning easy, a powerful and personal banner image to catch the reader's attention, and a confident and potentially controversial title that makes the reader want to learn more. "Broken" isn't a word we're used to hearing in the context of the ocean - it's poetic, symbolic, and new to our lexicon. And if someone saw the phrase "the ocean is broken" in a tweet, there's a good chance they might have hit Retweet without even reading the article because they agreed with the headline so strongly (admit it: you've done the same thing.).

There's certainly more to learn from this story - tell us your thoughts in the comments.

Shark Week Toolkit 2013

// This Toolkit is in progress.

// Have suggestions for what should go in here?

// Get in touch

Welcome to your home for shark-saving resources to help you defend, protect and celebrate sharks online during Shark Week (starting Sunday, August 4 at 9pm ET)!

There's a lot in here, so we've packed all the action-y goodies at the top, and pushed the background information to the end.

Table of Contents

I. Being a Super Engager

- The 2013 Shark Week Cheat Sheet (a one-page pdf packed with tips, info and the Shark Week schedule)

- How To Drive The Shark Conversation (Without Jumping It)

- -- Tips for effectively engaging online during Shark Week

- State of the Shark Online (“the Sharkinar”)

- -- Recording, Slides, and Notes from our Shark Week online briefings (July 16 and August 1)

- Myth-busting Resources

- -- Rapid Response Kit for Busting Shark Myths (particularly on twitter)

- Tips for Twitter and Facebook (from 2012)

- The best-est shark photos and videos to share and amplify

II. Background Information

- Shark Week 101 (Wikipedia) (By the Numbers)

- Shark Week Schedule

- Shark Week’s online campaign plans

- Shark Week Official Online Channels:

- -- Twitter | Facebook | Tumblr | Website | GetGlue (Social TV app)

- -- How to Engage Online with Shark Week [per Discovery]

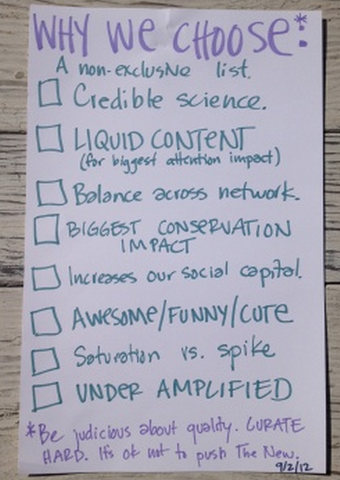

Why We Choose What We Choose (Upwell Curation Criteria)

Upwell is not a newswire for the ocean. It does not exist solely to pump out out retweets and links; if it did, it would be adding to the noise without necessarily increasing volume in a valuable way. So we subject the mass of possible topics to a triage test.

Version 2.0 of Upwell’s curation criteria, September 2, 2012

The first items to be discarded are those that don’t pass the scientific smell test; if the science isn’t credible, it’s out. Other considerations include:

Socially Shareable.

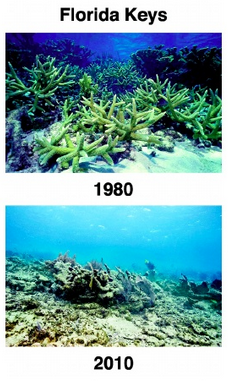

In order to be as effective as possible, it’s important to select topics that lendthemselves most easily to wide and willing dissemination, and spark conversation: what wedescribe as ‘liquid content.’ This can either be content that is already liquid—for example,content that is visual, awesome, scary, funny or cute—or that we can make liquid. The publication of a National Research Council report evaluating the federal response plan to ocean acidification is undoubtedly important—but seriously, what are you more likely to share with friends? That, or this:

Before-and-after pics. Good for US Weekly, good for Upwell.

Exactly.

Conservation Impact.

We’re a movement with a message. Not everything we share or amplify is Debbie Downer material. We also celebrate good news and successes and also highlight the awesomeness of ocean life. Even so, as part of our morning triage, we prioritize campaigns that have not just a generic conservation message, but the potential for specific impact: for example, petitions, seafood purchasing recommendations, etc. We find that content that is paired with action is more shareable.

Building Social Capital.

We calibrate our focus across issues, people and organizations in orderto cultivate trust, animate our network and maintain access to the most compelling oceancontent. We share content that comes from every corner of Team Ocean, with an effort toward spreading the love in a balanced way. If an important influencer asks us to share something, we do it. Generosity builds and maintains relationships, thereby increasing our social capital.

New Influencers.

We are always looking to grow our network and expand to new audiences.We prioritize content and campaigns that allow us to go beyond the choir and reach new influencers to enlarge the conversation and build the network.

Topical.

Sometimes the hook is an article in the New York Times that’s generating discussion onTwitter. Sometimes there is no hook, and we have to find it, or make it. Tying ocean content with events like the Olympics, Rio+20 or Lance Armstrong’s steroid use helps up the shareable quotient.

Spikeability.

Has a news story or piece of content already reached its saturation point? If something has already received a lot of coverage and attention, we judge whether it's worth our effort to create another spike in attention (like an aftershock) or if it's already been shared by as many people as it will be (saturated). Often, the best way to judge whether something is spikeable is to ask whether the content will be shared two or three degrees out of our network. Will it generate interest and conversation beyond Team Ocean?

Under Amplified.

We look for awesome news and content that we think has been egregiously under-amplified. Sometimes a hot piece of news just wasn't packaged in the right way. We mine our network and find the awesome stuff that few have seen, and we repackage it to go farther.

Top Shark Influencers

Here comes Shark Week! August 4, 2013 will kick off the biggest spike in the shark conversation all year. As background research for our Sharkinar, we've again compiled a list of some of the most effective and influential drivers of social media shark discussions. We will keep this list up to date over the course of Shark Week to reflect the latest stats and show who's influencing the conversation.

Subscribe to Upwell's "Shark Influencers" list on Twitter to keep tabs on these influencers from the comfort of your own Twitter feed.

Alisa Schwartz

Followers: 6,490

Twitter Bio: Scuba diver-outspoken marine conservationist w/shark focus. No Blue = No Green. Total Ocean Devotion! Follow @sharkangels @JoeRomeiro @epicdiving #savesharks

Website: http://www.sharkangels.com

Alisa is one of the most engaged individuals posting online about shark conservation, tweeting many times daily, including multiple article and news links.

David Shiffman

Followers: 10,056

Twitter Bio: I am a marine biologist studying shark conservation and a blogger. I support science-based management and sustainable fishing, and do not support direct action.

Website: http://southernfriedscience.com

David is one of the most active of shark experts in social media, frequently engaging his followers in conversations on science and policy and compiling some of those discussions in Storify form. He is also a frequent blogger at Southern Fried Science.

DianeN56

Followers: 8,401

Twitter Bio: A Midwest Ocean and Animal Lover ゅゆゅ° ≈≈≈ °ه~ゅゆゅ〜~○°○○ I Love The Sea and Everything In It and Will Support Any Who Pledge To Protect It!

NRDC

Followers: 96,853

Twitter Bio: The Earth's Best Defense

Website: nrdc.org

Oceana

![]()

Followers: 77,774

Twitter Bio: Working hard to protect our oceans. Fighting against offshore oil & destructive fishing. Fighting for clean energy, sharks, & turtles.

Website: oceana.org/act

Shark Advocates International

Followers: 1,499

Twitter Bio: A non-profit project of The Ocean Foundation dedicated to promoting science based conservation of sharks and rays. Tweets from founder, Sonja Fordham.

Website: http://sharkadvocates.org

Project Aware

Followers: 14,732

Twitter Bio: Protecting Our Ocean Planet - One Dive at a Time

Website: http://www.projectaware.org

Engages scuba divers across the world to become involved in two principal project areas: marine debris, and protection for manta rays and sharks.

Richard Branson

Followers: 3,321,928

Twitter Bio: Tie-loathing adventurer and thrill seeker, who believes in turning ideas into reality. Otherwise known as Dr Yes at @virgin!

Website: http://www.virgin.com/richard-branson

Rob Stewart

Followers: 10,613

Twitter Bio: Biologist, shark lover, photography and documentary filmmaker. Creator of Sharkwater, founder of non profit @uc_revolution working on second movie, Revolution

Website: http://www.sharkwater.com

Rob boasts a wide presence online, not just through his own Twitter handle but also that of @uc_revolution (the website of which is www.unitedconservationists.org), an organization that among other things campaigns against shark finning. His documentary, Sharkwater, received numerous awards. Also involved in Shark Angels.

WildAid

Followers: 16,486

Twitter Bio: WildAid is a wildlife conservation non-profit focusing on reducing the demand for endangered species products including from sharks, rhinos, elephants, tigers.

Website: wildaid.org

Pew Environment

Followers: 8,324

Twitter Bio: We work globally to establish pragmatic, science-based policies that protect our oceans, preserve our wildlands, and promote the clean energy economy.

Website: pewenvironment.org

Want more shark influencers? Check out and subscribe to our Shark Influencers Twitter list for an even longer list of people talking about sharks!

Upwell's Pilot Report (aka 165 pages of awesomeness)

In our first year, our experimental pilot project, Upwell, charted new territory to engage a larger and more diverse audience in the ocean conversation and to elevate the ocean while not elevating any particular organization or perspective. We have done this by quantifying the level of the ocean conversation across a range of topics and measuring the impact of engagement on the issue, a first for the strategic ocean communications initiatives.

During our first year of incubation, Upwell successfully pioneered the development of new methodologies in social monitoring, demonstrated success in elevating the ocean conversation above the baseline, earned praise for a non-branded approach to campaigning from social media thought leaders and attracted additional philanthropic interest in expanding the project beyond the intent of the pilot phase across a range of environmental issues. We are grateful for the Waitt Foundation's significant initial investment, which provided the vision and commitment to launch this entrepreneurial initiative and are appreciative of other funding we have received for the project.

Over the past month, we've been sharing many of the insights from our pilot year of working to make the ocean famous on the internet. Many of the recent posts here have covered elements of the report including defining social mentions, conversation metrics for Overfishing and Sustainable Seafood, our distributed network campaigning method, the Upwell campaign lifecycle (an awesome idea, requested by Ayana Johnson), our spike quantification of the ocean conversation, and Upwell's ocean conversation Baseline methodology.

We've also shared our findings on other blogs like Lean Impact and Beth Kanter's blog, all derived from a massive report we wrote in January and February. We're talking massive! This sucker is 165 pages. We hope the community of ocean communicators and social changemakers find value in our research and findings. We'd love to share it more widely. Email us with your guest post offers and Today Show opportunities at tips@upwell.us. We'd love your feedback!

Read the Upwell Pilot Report, by Rachel Weidinger, Rachel Dearborn, Matt Fitzgerald, Saray Dugas, Kieran Mulvaney and Britt Bravo.

Download the Executive Summary here.